The words are Leon's and they occur in one of the letters he wrote me shortly after I left Moret and was back in London. Rowley was now in Montparnasse and judging by his fairly frequent letters to me he continued to lead his usual life. His letters sometimes contained descriptions of parties; once the news that Willy Gilman had died from an overdose of Veronal. Now and again he mentioned he was working.

Sometime after he returned to Montparnasse, Rowley took a studio in the rue Daguerre, which is on the way to the Porte d'Orléans, near the huge bronze Lion de Belfort. It is within easy walking distance of Montparnasse.

And about that time Ruth Hallmann went to live with him. One of his letters told me they had settled down in the studio, they had got a cat - he loved cats - and everything was 'swell'. I hoped that maybe he had found the type of woman he thought he needed. The news that Homer Bevans lived close by was, however, disturbing. I knew my Rowley by now. All was well when he had been in Moret with the Finn until Homer and his gang helped to drive her away. I had, it is true, found it impossible to stop Rowley drinking, indeed I hadn't tried, but I succeeded, more or less, in helping him to put some limit on it.

Ruth stayed with Rowley until he died in 1934. She was with him when he came back to England in 1932. I saw her then for the first time. Early one morning I went to King's Cross to meet them. Rowley looked ill and exhausted and Ruth and I had almost to lift him out of the train.

Ruth was a big, fair-haired Scandinavian. She had large yellowish brown eyes and she stared very hard at me. She spoke English with an accent not easy to understand. During the long taxi drive to my studio in West Kensington she told me how often Rowley had spoken to her about me. 'You are his best friend,' she said, looking at me with her bold eyes. I felt she was summing me up, trying to find out how much influence I had over Rowley, for she treated him as if he belonged to her utterly. Rowley sat humped up in a corner of the cab. He complained of the cold although he was wearing three overcoats, one on top of the other. He had an alarming cough and his eyes looked feverish. It was some years since I had seen him, and I saw a terrible change.

At the studio Ruth helped me cook bacon and eggs on the gas ring and we made tea. After the meal Rowley sat on my old green sofa and cheered up a little, but he still coughed terribly.

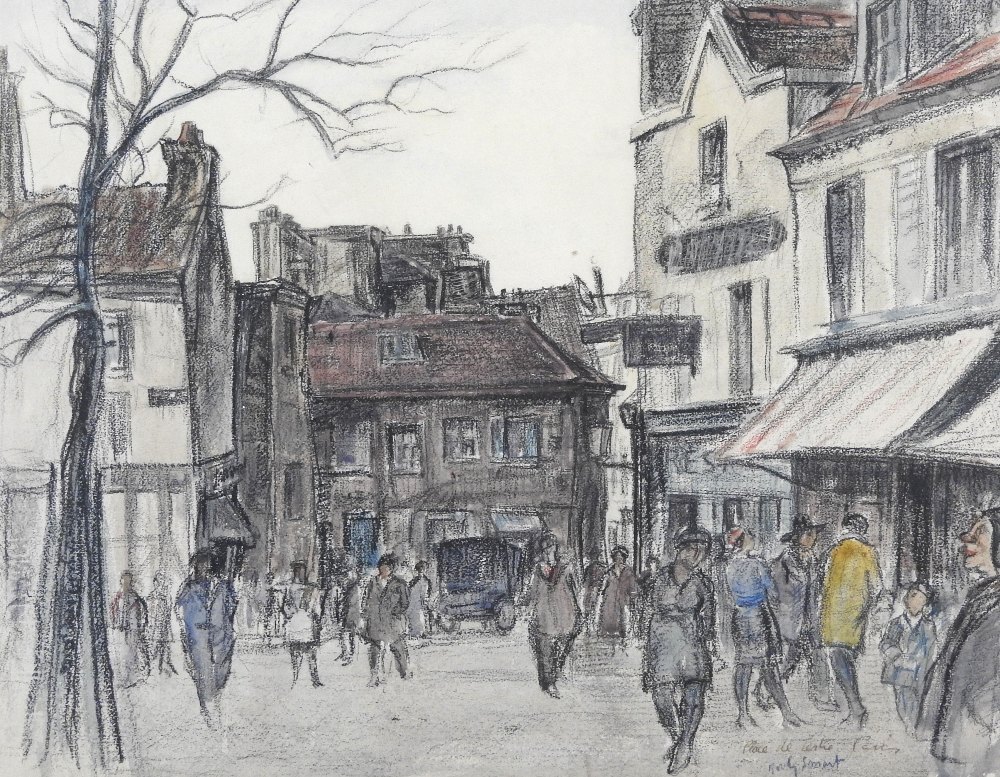

There was a portfolio among his luggage. It was full of watercolours of Paris streets, many of them crowded with figures. I thought they were among the finest things he had done, and I think so still. His art had, like himself, changed greatly. These drawings possessed, for me, an almost overpowering sense of sadness. Yet they were full of life and movement. The sunlight of Moret and of the Paris oils I remembered had gone. Rowley had dug deeper, reached far beyond his previous concern with the accidental light and shade, the charming coloured effects of sunlight. Here was the very soul of the streets. In design they were masterly.

Rowley told me what a difficult business it had been getting away from Paris. He owed rent and Ruth and he had managed to get a few paintings at a time past the concierge, leaving them with various friends. I forget how they finally managed to take their luggage away but I remember him telling me that on the way to the station they kept on telling the driver to stop so as to pick up various pictures and only just arrived at the station in time for the train. It had been an exhausting business, and he did not know how he would have got on without Ruth.

They had arrived at such short notice that I had no time to find them a room. There was no bed in the studio for I was only using it to work in. I remembered an old friend of Rowley's, Mrs Dockrell, and we all went to her little antique shop in Kenway Road, Earl's Court. She knew plenty of people who let rooms and we were able, with her help, to find a place that afternoon. Not long after, Rowley moved to a couple of furnished rooms in Paultons Square, Chelsea. They had not been there long when the ceiling fell down. Luckily one of the Wentworth Studios in Manresa Road was vacant and for some months Rowley lived there with Ruth. He did a few oils of Chelsea streets and some flower paintings in the studio. His health was getting steadily worse. Some days he was too weak to get up. Although he would not admit it I think he knew by now that his lungs were going fast. He smoked and drank comparatively little, chiefly I think because it no longer gave him any real satisfaction. A morbid streak began to appear in him, yet he kept his sense of humour only now it had a quality of grimness. There was a song, very popular just then, called 'Ain't It Grand To Be Blooming Well Dead'. Rowley never tired of putting it on the gramophone. He wished Danny was there to play it on his ukulele. He made a large watercolour of a funeral procession and he named it after the song. He seemed to gloat over it.

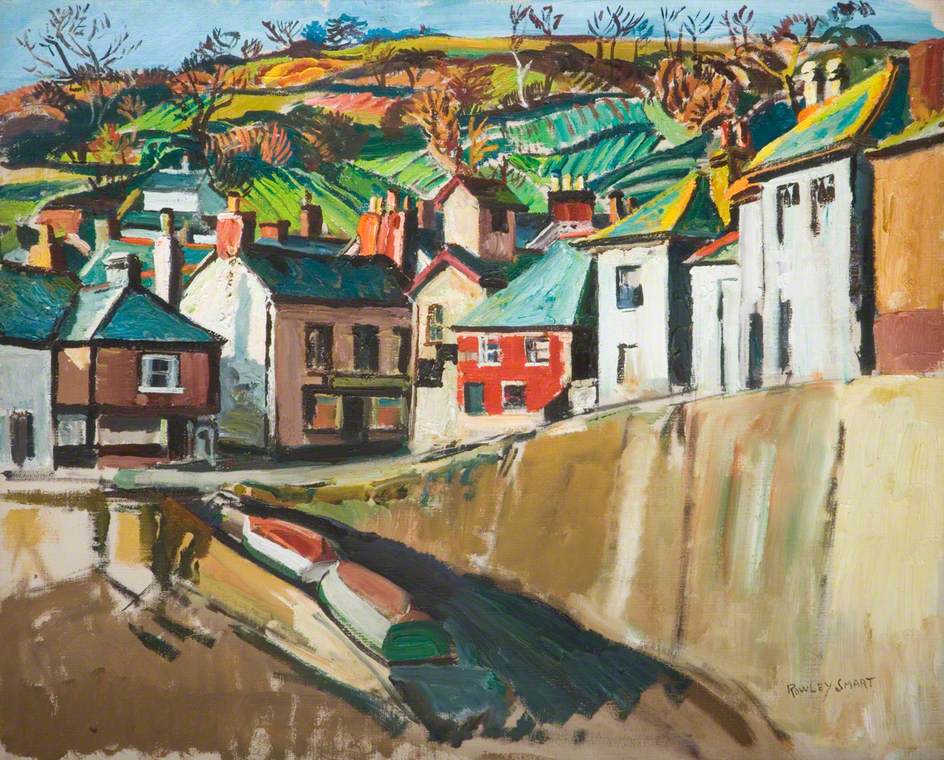

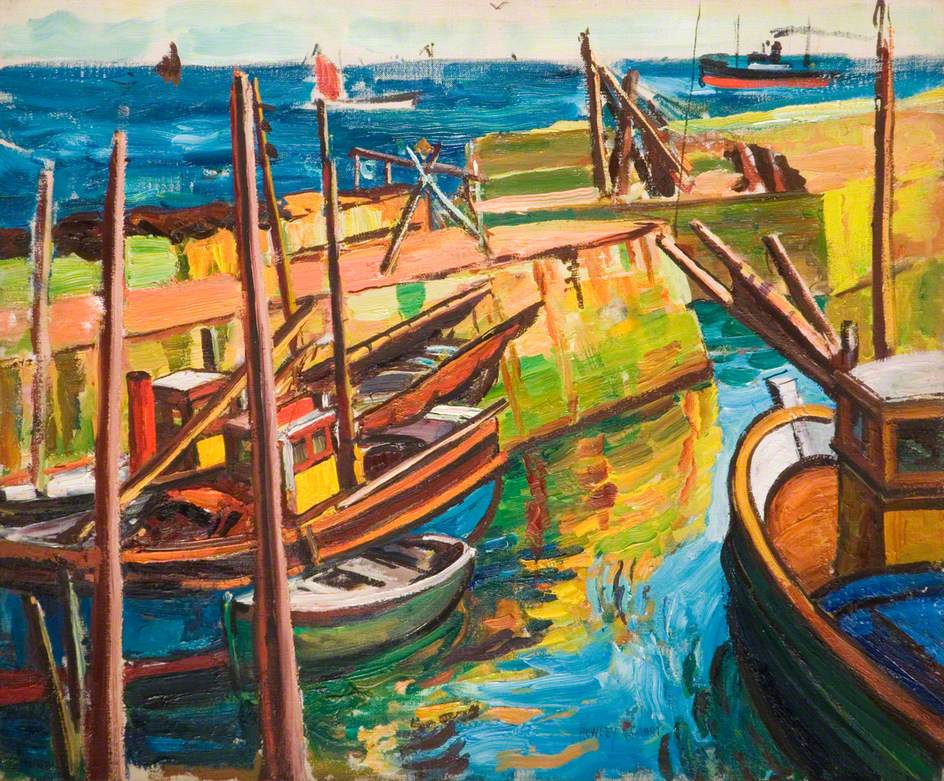

He talked very often of his health. He consulted doctors. His friend Doctor Stross* came to see him. A change of climate was thought necessary and Ruth took him to Mousehole near Penzance, Cornwall. Although he wrote telling me how he loathed being there his health undoubtedly improved for a time, and he painted some fine watercolours and a few oils. In these oils he abandoned the almost pointilliste technique he had used in Moret and he now worked with a fully loaded brush with plenty of impasto. They were strong and amazingly vigorous.

* Dr Stross, Rowley's friend, doctor and patron Barnett Stross (1899-1967) GRH

In 1933 he had an exhibition at the Leger Gallery of the Paris watercolours and the work he had done in Cornwall. Rowley came back to London for the show and stayed at the Eiffel Tour Hotel*. He was sick of Cornwall. He said the Cornish were the most miserable lot of people he had ever lived among, and he was a fool to have gone there, also the climate was filthy and would have surely killed him had he stayed there any longer. The improvement in his health was only temporary for his disease had now developed all its terrifying characteristics, playing with its victim, giving him sudden bursts of energy and hope, only to leave him utterly prostrate, coughing up blood-stained phlegm. He had finished with smoking and he could not even bear the smoke from other people's cigarettes, it made him cough. I never smoked when I was with him. He had grown a full beard, and it gave him a wild, prophet-like appearance, with his hawk-like nose and keen piercing eyes. He lost weight and became pitifully wasted. Ruth was devoted to him in her way but I could not help wishing that she had discouraged him from going to the Fitzroy on evenings when he felt a little stronger. It would do him good, she said, and cheer him up. It is true that he did regain, for a few hours, some of his former good spirits, and he never had more than two or three drinks, but the crowded, smoky atmosphere of the ill-ventilated Fitzroy was hardly the place for a man rapidly approaching the last stages of TB.

* The Eiffel Tour (Tower) Hotel at 1, Percy Street, Fitzrovia, London, later called the White Tower Restaurant and now called The House of Ho. GRH.

Perhaps by then it did not matter so much, for I believe it was too late to do anything for him, the disease had got too firm a hold; but his energy was so short-lived, and when he had walked the few steps from the Fitzroy to the Eiffel, leaning on me with all his slight weight, I had to take him in my arms and carry him up the many flights of stairs to his room, for the Eiffel was an old-fashioned place and had no lift. Then as he lay on the bed, coughing and spitting blood, I used to wish with all my heart that Ruth would manage things differently, it should not have been so difficult. Rowley was now too feeble to insist on his own way for long. But the truth was that Ruth loved the atmosphere of the pub herself. Of course Rowley hated being left alone and she did spend a fair amount of her time with him. There is her point of view to be considered, yet I find it hard to forgive her. She never tired of saying how much he meant to her, how greatly she loved him. I have known more devoted women.

Ruth did so much for him that the things she left undone were more noticeable in consequence. I believe that she was half starving when she first met Rowley. Something about him must have appealed to her, his helplessness perhaps; she is so big and strong, so capable. She is said to have picked him up, literally, in the Dingo one night when he was very drunk, found out his address from the barman, or maybe from Homer, and taken him back to the rue Daguerre in a taxi. And there she found he had some sort of a home with furniture and a bed. The paintings were good too, very good. I have great respect for Ruth's judgement in art. She must have felt that here was a chance of comparative security. She had been knocking about Montparnasse for quite a time, frequenting the all-night bars and, I have heard, snatching bits of sandwiches left on the tables. There was a husband somewhere, in Denmark I think, a very brilliant draughtsman, for I once saw a reproduction of a drawing by him. She was never Rowley's mistress; she told me herself that he never had any sexual relations with her, and had not Rowley himself told me more than a year before he met her that he had 'finished with that sort of thing.' I had rather doubted it at the time, he was only forty-one, but subsequently he told me he had caught syphilis many years before. It was the usual story. He had become bored with the treatment, then the disease appeared to subside, and he thought, or wanted to think, he was cured. Possibly it was again giving him trouble when he mentioned it to me during that summer of 1928 in Paris.

Ruth's relationship to Rowley always appeared to be that of a mother. I am sure that her healthy woman's instinct to protect, when faced with physical weakness or ill health, was very genuine, but her natural cupidity played a by no means inconsiderable part. Rowley was pitifully grateful to her for all she did. She seldom lacked money and he was always generous.

Not long after the exhibition at Leger's finished, Rowley, on his doctor's advice, made up his mind to go away. He decided on Spain, he needed the sun. The tickets were bought and all arrangements made. I went to the Eiffel to say goodbye to them for they were leaving the next morning. One of Rowley's friends had promised to call with his car to take them to the station.

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -9

Clifford Hall at 2 years old

Paris Street Scene by Rowley Smart.

Portrait of Ruth Hallmann by Rowley Smart.

Mousehole by Rowley Smart. Now in the Keele University Art Collection.

Street in Mousehole, Cornwall,1933, by Rowley Smart.

Mousehole, the Harbour, by Rowley Smart. Now in the Keele University Art Collection.