INTRODUCTION

Clifford Hall sold his first painting when he was a lad of 18. He was working on a little panel down by the banks of the River Thames, busy adding a few finishing touches to his latest creation, when a workman came by and stopped to look at what he was doing.

'I work at that factory' the man said, pointing at a building in the picture.' I like it. I'd like to buy it. I can't afford much, I don't suppose you would take five bob?'

'Oh yes I would!' exclaimed the young artist, and the deal was done.

Many years later, not so very long before he died, a young woman with short dark hair and wearing a black sweater and paint-stained trousers saw Clifford as he was walking along Westbourne Grove and asked him if he was Clifford Hall. He admitted he was. She told him she was so glad to have met him, as she had seen his recent exhibition at the Hamet Gallery and thought he was the greatest painter in England.

Bewildered, he told her that this was ridiculous. But she insisted that he was, and stayed at his side as they walked from Bayswater to Notting Hill Gate, enthusiastically expressing her admiration of his work.

Little wonder, perhaps, that such intense admiration from a passing stranger in the street should leave him feeling somewhat bewildered. The show she had been to see had not been a great success; far less so than his previous one two years before. A poor review, from a prominent critic, who had waxed and waned in his opinions of Hall's work for years, had more-or-less seen to that, as most of the other critics, just like so many sheep, had pretty much followed this man's lead.

Clifford Hall had lived to paint and draw, and he had worked hard at it all his life. Ever the 'struggling artist', he was still neither truly famous or completely unknown. His reputation, such as it was, had waxed and waned, as had the critic's reviews of his work. Indeed, upon a few occasions he had found himself paying the proverbial 'price of fame'. For example, when he married his second wife, Ann, in 1956, the private event had been considered sufficiently newsworthy by the London Evening Standard for them to publish an uninvited photograph of the couple leaving the Registrar's Office. It had been taken by a sneaky gentleman of the press after a scuffle with the best man. Then, following this embarrassing incident, Clifford had received a letter from his previous wife, Marion, accusing him of 'execrable taste', as if he had sought the publicity himself rather than tried to avoid it. But subsequent to this, ironically, no photos of him or his work, officially or unofficially taken, had ever appeared in the Evening Standard again.

Of course, being the struggling artist that he was, for much of his life he had had to resort to the teaching of drawing and painting to make ends meet: No great shame in that, an artist teaching art, as most artists, even the greatest, will spend some of their time instructing others, endeavouring to pass on their hard-earned knowledge and skills to the next generation. It could almost be deemed churlish and irresponsible for an artist of his ilk not to have given up some of his time to such a noble cause. After all, had not Walter Sickert, Sir George Clausen and Charles Sims RA spent a little of their time in teaching him when he had been a student at the Royal Academy Schools? But then there had been a few years, during those dark days of the Great Depression and World War 2 when hardly anyone was buying paintings, when he had had to resort to teaching full-time. No matter that those were desperate times, this still felt like an awful failure to him; an appalling and abject condition he must escape from as soon as humanly possible.

Most of the time, however, he had been able to manage to get by with just teaching part-time. Yet now he had come to loathe that too. Not because he wasn't good at it - he was. Not because he didn't have a few worthy pupils - he did, but because this teaching business robbed him of so much precious working time. So, his holidays were invariably working holidays; and his weekends often the most industrious of his days. And industriousness was a thing of great importance to him; he believed an artist must work and work to produce as much good work as he can. So he would often chide himself for not doing enough work and tell himself he must find a way to do more.

His exhibition at the Hamet Gallery, Cork Street, London W1, had been his eighteenth one-man show, his twelfth or thirteenth show depending on how one views his first at the St Martin's Gallery in 1929, to take place in London's West End. There had also been five or six joint exhibitions with one or two of his artist friends, as well as numerous contributions to major group exhibitions in the UK and abroad. One could almost be forgiven for not understanding why he was not a 'household name' - if, that is, you were someone not that familiar with the vagaries and vicissitudes of the art world.

In the past, he had had a long and quite financially successful association with Lillian Browse, the 'Duchess of Cork Street', which had continued throughout her early days at the Leger Gallery, Bond Street in the 1930s, followed by her time at the National Gallery during the War and subsequently right up to his third and final show at Roland, Browse and Delbanco in 1950. But this relationship had then mysteriously dwindled to the point where Roland, Browse and Delbanco would only occasionally take one or two of his little panels for inclusion in their 'Christmas Present' exhibitions. Why had Roland, Browse and Delbanco stopped, almost stopped, that is, dealing in his work after such a long and profitable association? Understandably, all the other dealers he went to wanted to know, but he had been much too much of a gentleman to reveal the real truth of the matter.

However, despite this troublesome issue, he had found other dealers to work with. But none of them had suited him as well as Lillian Browse had once done and it had taken him twenty-two years since his last show at Roland, Browse and Delbanco to get another show in Cork Street. And now it was a worry for him that it had not gone a great deal better. Not least because, if it had, he could at last have given up the damned teaching altogether. After all, he was 68 years old now, not in the best of health, and still had so much more he wanted to paint.

* * * * *

The young woman who told Clifford he was the greatest painter in England was clearly the artist Barbara Dorf (1933-2016). We know this as he wrote in his diary:

She knew I lived in Newton Road and told me her name was Dorfer, Barbara Dorfer I think, and could she come and see me? I could hardly say ‘no’. I thought her too intense – a little unbalanced perhaps.

It is not known if Barbara Dorf went to his studio before he died, or if he ever met her again. If she did, he made no mention of it. It is also not known if she persisted in her very high opinion of him. One can only hope she did, as it is really no small thing for a painter to accost a fellow painter in the street and tell him that he is the greatest painter in England.

Whether or not the Duchess of Cork Street dropped by the Hamet to view Clifford's exhibition in June 1972 is not known either. It seems unlikely, for if she had, it would probably not have escaped notice. She did phone him some weeks earlier, seeking the address of one of his friends who owned a William Nicholson painting she wanted to borrow for an exhibition she was organising; so, there can be no doubt that she knew about the Hamet show. There is also no doubting that Lillian Browse was the most important art dealer in Clifford Hall's life, for her name appears in his journal more than ninety times. In stark contrast to this, when she came to publish her autobiography in 1999 she did not mention him by name so much as once. There he is described (on page 103) merely as an 'appropriate person' she 'found' to write the short essays (the biographical introduction to the illustrations) for the book on the French artist Constantin Guys, published by Faber & Faber in 1945, for which she had been the general editor.

There is, of course, no chance at all that Clifford Hall's name could have possibly slipped her mind. She was clearly slighting him. Possibly not consciously. But slighting him nonetheless.

The online publication of Clifford Hall's complete and unabridged Memoirs and Private Journal has begun. Clifford Hall Memoirs

Cliford Hall on the Web: LINKS to other relevant pages

(NB Quite a few of these web pages currently include some inaccurate and misleading information. This includes the Wikiepedia page, so this is quite understandable.)

Dedicated to the life and works of the British artist Clifford Hall, ROI, NS (1904-1973)

We have started publishing here the extant memoirs and private journal of the painter Clifford Hall in their complete and unabridged form.

We will also be publishing a large amount of related correspondence and other written material.

It is also our ultimate aim to complete an online illustrated catalogue raisonné of his works. We would very much like to hear from anyone who owns, or believes they own, a picture or pictures by Clifford Hall.

The Girl with a Cat, 1969, by Clifford Hall. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre.

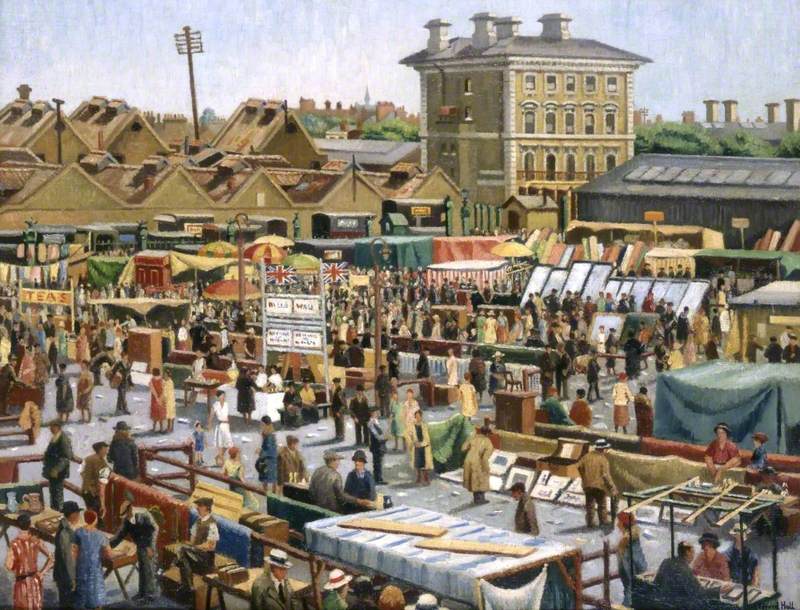

The Caledonian Market, Copenhagen Fields, London, 1933, by Clifford Hall. Museum of London Collection.

A Street in Malakoff,1928, by Clifford Hall. University of Hull Art Collection.

Street Scene in Antwerp, 1967, by Clifford Hall. Private Collection.

Resting Nude by Clifford Hall. Private Collection.

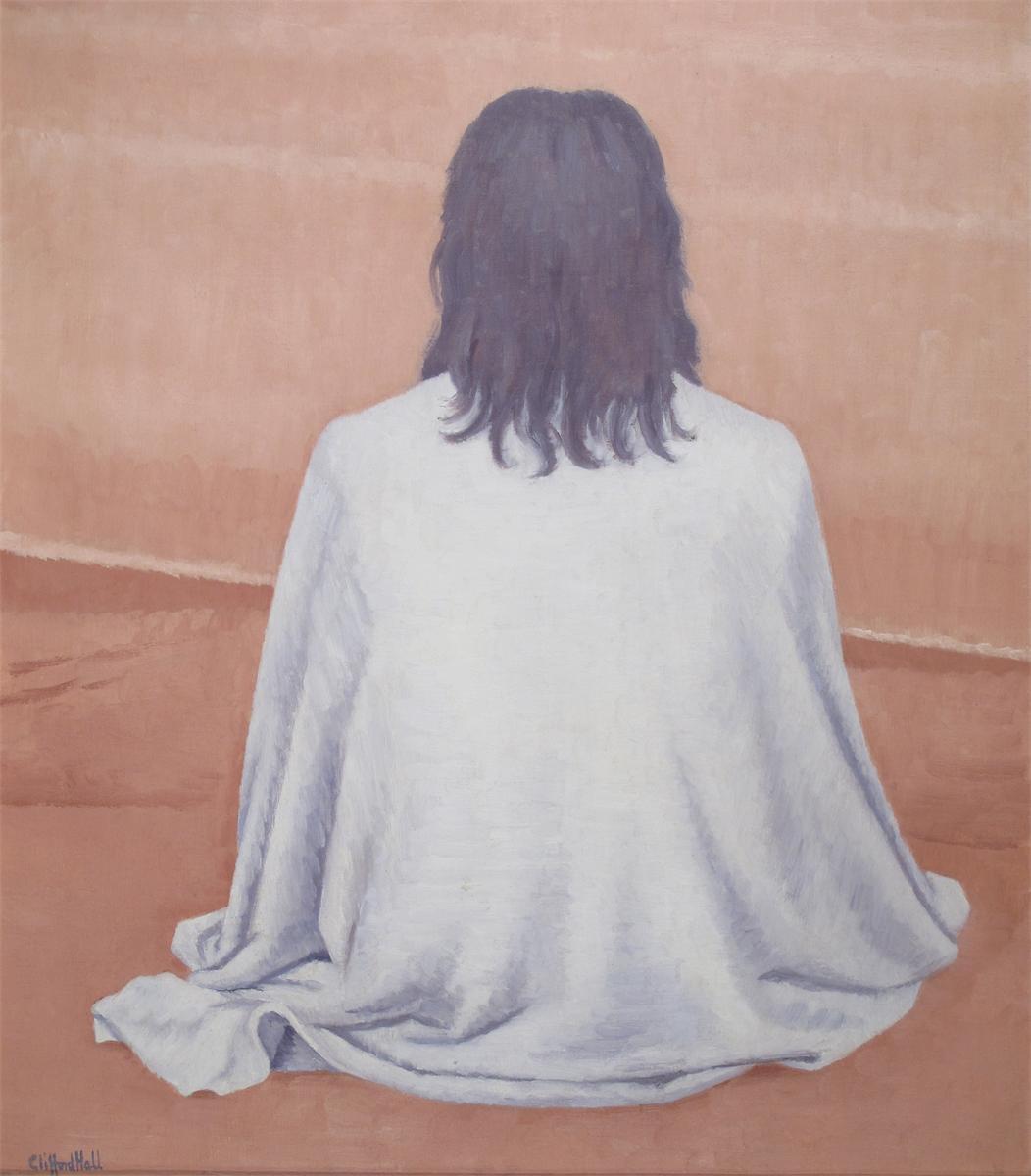

Bather Facing Away, circa 1965, by Clifford Hall. Private Collection.