During 1927 whilst I was still at the RA Schools, I had a number of portrait commissions. I was able to pay the rent of a large room in Twickenham Park which I used as a studio. I saved, for my rent was low and I was also getting money from a Landseer Scholarship I had won at the schools.

Since my first short visit to Paris in 1925 I had dreamed of going there again, for a long stay. When still a schoolboy I had read Murger's 'La Vie de Bohème', and ever since I had thought of Paris and I was sure that nothing had changed since the days of Marcel, Mimi, Rudolph and the rest.

That was how we should live, I had decided. I too would spend my money carelessly when I had it, and get along somehow when it was all gone. Mimi awaited me. I was very romantic, and eager to get away from home.

At the beginning of 1928 I had saved nearly £150. Edwin John* was already in Paris and wrote to remind me I had promised to join him when I had enough money. Sickert was no longer teaching at the Academy, even Sims had gone, and the schools were dull and uninteresting. Edwin wrote again. He had found a place, very cheap and not far from Montparnasse. I was eager to go. My father saw me off. He gave me a sovereign, a golden sovereign, in case I ever really needed it, and told me to be careful to avoid women.

* Edwin John (Nov 27 1905 - Feb 2 1978) the fourth son of Augustus John and his first wife Ida Nettleship. GRH

During most of 1928 I shared a studio with Edwin in Malakoff, a working-class suburb of Paris. It was situated just outside the outer boulevard. We could walk from Malakoff to Montparnasse in about three-quarters of an hour, or we could go by tram. Our studio was fairly large and had a gallery bedroom. We did not have much furniture. Two single divan beds, one chair, a table, a couple of easels and an old wooden box. There was a built in wash basin with running water and a large, very ornamental iron stove. We kept a heap of coal on the floor, in a corner under the stairs. A few drawings were pinned on the walls. Very austere.

It was one of several in the rue Leplanquais and next door our landlord, his sons, and several workmen produced quantities of sculpture à machine, a horrifying method involving the use of a sort of drill worked by compressed air. The drills made a good deal of noise. The men worked very hard and were covered with powdered stone. They wore round paper caps on their heads to keep the dust out of their hair. They often sang as they worked.

Our landlord was a charming old man. I used to see him every evening in the market place, smoking his pipe.

'Ah Monsieur Clifford,' he always said, 'off to Paris again.' He spoke as if I was undertaking a long, long journey, yet Paris was only a bare fifteen minute tram ride away.

'And have you never been to Paris?' I asked him.

'I went there once. Someone died and I had to see a lawyer. But I prefer to remain here.'

Just inside the gate through which one passed from Malakoff to Paris was a large tract of waste ground. Here the gypsies sometimes camped with painted wagons and shabby tents. Gypsies from Spain, from Roumania. Straight lithe girls in long flowered dresses with a streak of thin red braid plaited into their hair. Terrifying old women, huddled up, smoking a pipe, grim reminder of what the girls would in time become. Insolent, handsome young men, and dignified old grandfathers with dozens of silver coins on their watch chains. Many little children in summer time, stark naked, golden brown firm little bodies, running everywhere.

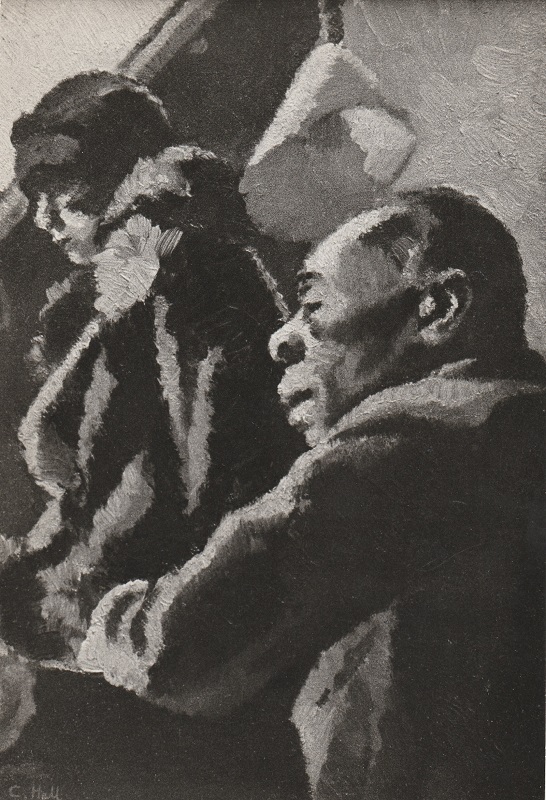

Edwin and myself used to draw in the Cours Libre at the Grande Chaumière several times a week. For a short time I worked in André Lhote's studio near the Gare Montparnasse. On Monday mornings the big atelier was crowded with students. The model waited. A few minutes before 9 o'clock, Lhote would suddenly appear through a door opening on to the balcony at the far end of the studio. He was a little man with a charming smile, dressed in a dark lounge suit with a coloured silk handkerchief neatly arranged round his neck. He beamed at the faces upturned towards him. 'Bonjour mes enfants,' he said, and 'Bonjour Maître,' came the reply. I think he liked it. The master tripped down the stairs from the balcony and into the studio. He posed the model and gave a short talk on how he thought we should plan work during the week. We did not see him again until Saturday, the last day of the pose, when he reappeared still smiling and gave a few words of criticism to each student.

I did not stay there very long. I had had enough of schools and I began to work more and more on my own. Sometimes in the Malakoff studio, sometimes in the streets round about. But I continued to draw at the Cours Libre. I think it was at the zinc bar of the Dôme, where we sometimes went for a drink when the drawing class was over, that Edwin introduced me to Rowley Smart.

In those days Rowley was living in Montparnasse and he was never very far from his favourite haunts, the Dôme, the Rotonde, the Dingo Bar and the Select.

He was clean-shaven and wore his hair fairly long, hair that was just beginning to grey. A short, slight little man with a very big nose, lively blue eyes, a fresh complexion, a weakish chin and the most beautifully shaped hands I have ever seen.

It was summer when I first met him, and he wore an open-neck shirt, flannel trousers, a check jacket and a fawn coloured hat with a very wide brim, chapeau d'artiste, as they were called. On his feet, a pair of rope soled canvas beach shoes.

We had drinks, and Rowley was sure he had met me at some party or private view in London a year or so back. I certainly had no recollection of having seen him before, but I agreed that he was probably right. I said this to please him, for I had already made up my mind that we would meet again. He seemed interesting. I guessed that he had taken a liking to me. Edwin was morose, and sometimes would not speak for days on end - a difficult companion.

Rowley and I saw each other frequently after that first meeting. Indeed it was impossible not to come across him somewhere in Montparnasse.

At times during the afternoon I would see him sitting on the terrasse of some café, a 24" x 20" canvas propped on a chair in front of him, busy painting a view of the street. Drink and cigarettes were on a table by his side. His brushes were, to me, shockingly kept, I never saw him wash them, and his palette had obviously not been cleaned for years, but he worked with bright colours in a high clean key. These street pictures were complicated things in their way. Perspective, chimney pots, crazy French skyline, windows, shutters, café awnings, chairs, trees, people, shadows.* He would make a few guiding lines in pencil, very faint on the white canvas, and then commence to draw the whole design in cobalt blue, delicately touched but using no medium. Then he started to paint in the colours, but contrary to anything I had seen before, he commenced at the top and worked down towards the bottom, finishing as he went. He would spend four to six sittings on such a canvas, never working for more than two hours at a time, and always choosing a sunny day. His oils at that period were frankly influenced by the Impressionists.

* See Quai St Michel, Paris 1928, oil on canvas, Manchester City Art Gallery. The painting currently (in the year 2005) hangs in Room 10 and nearby hangs a portrait of Rowley Smart by Adolphe Valette, his teacher, who was also the teacher of L. S. Lowry. JH

When the sun did not shine and it was consequently impossible to continue a particular painting, Rowley could find nothing better to do than to sit gloomily at some café drinking, smoking and cursing the weather, declaring France was developing a climate as bad as that of Manchester, his home town, the 'dirty city', where it rained always and it was impossible for a man to paint, much less get a drink when he wanted one. By early evening of a wet or dull day the drinks would have made him cheerful and most of the night would be passed with more drinks and singing at the Dingo, rue Delambre, with American sailors, French girls and people he referred to as 'booze-fighters'. He could then stand a huge quantity of alcohol - wine, Pernod, brandy - and although he was drunk most nights he was not 'paralytic' as we said in the Quarter; that is unable to walk or even speak. No, Rowley was a merry drunk, dashing off obscene rough sketches (these were usually grabbed by someone of the party. I rescued a few myself.), laughing and roaring out dirty songs, making up fresh verses as he went along. A clown, but an amusing clown, and Lew Wilson who ran the Dingo knew Rowley was an attraction. He was good for business, and Lew gave him drinks when he was hard up, lent him money and hung the bar with his paintings. For some months the Dingo was literally covered with Rowley Smart oils. Wilson had lent Rowley several thousand francs and the pictures were there as security.

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -1

Clifford Hall photographed in Paris in 1928

This portrait of Sir Henry Norris, painted in 1927, was probably the most high-profile portrait commission Clifford Hall completed before he closed his studio in Twickenham and departed for Paris. (no colour image currently available)

'Mother and Daughter' by Clifford Hall. Painted in the Cours Libre at Colarossi's, Paris 1928. (no colour image currently available)

'Man and Girl' 1927 by Clifford Hall (no colour image currently available)

.jpg)