The Artist and the Circus

This is a transcript of an article by Clifford Hall which was published in the Winter 1936-37 edition of the CFA's first magazine "The Sawdust Ring" (VOL. IV No 10).

I am at the circus, tucked away in a corner among the audience, my sketch book ready. It is an ideal position from which to work, for the audience is as interested in the performance as I and no one disturbs me.

I hear the opening bars of the faintly oriental music heralding the entrance of the elephants. Hurriedly I turn back the pages of my book and prepare to add a little more to the sketches begun perhaps a week ago. Night after night I look forward to this moment which, when it arrives, is far too short. Yet I have added to my sketch and stored up more of this fascinating subject in my memory.

Although at times it seems almost impossible to express the movement and colour of the circus, there is the satisfaction of knowing that the performers, whether human or animal, go through their acts with precisely the same movements, order and positions at every show. When I have left off one night, I can resume again the next, knowing that everything will be just the same.

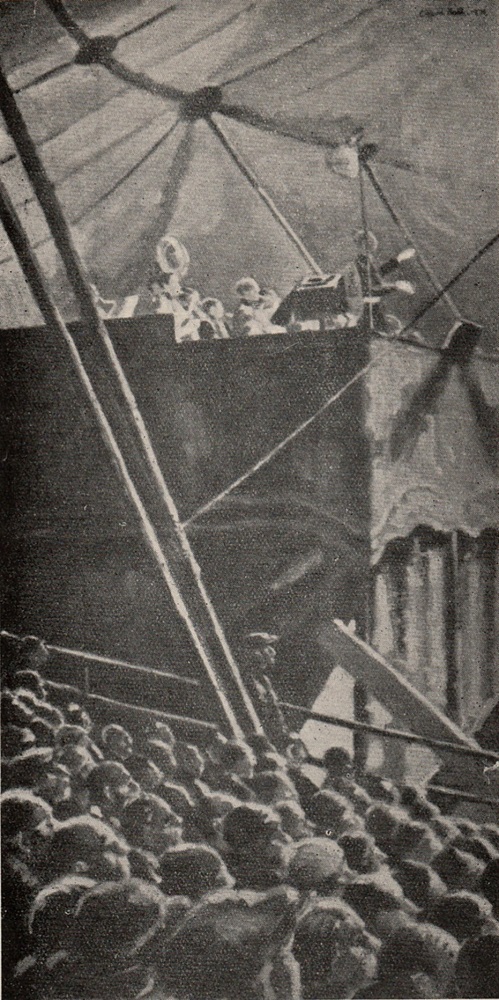

When the elephants finish their act, I leave my seat to move to another part of the house: on my way, walking along the wooden gangway, high up at the back of the seating, I am caught by the magnificence of the orchestra towering in front of me. Fool that I am not too have seen before that here as well as in the ring is beauty! I must at once start a drawing of this new discovery, which already exists in my imagination as a finished painting. I am now lost in the performance. The faces of the watching audience, their varied expressions as changeable as the light which plays on their features, joins them with the orchestra into a wonderful and exciting design. It maybe that Bombayo is doing his hazardous somersaults on the bouncing rope; perhaps Bartoni is swinging high in the air, but for me it is the intent faces, the band and the gay music which guides my hand. Here, for the time being, is the drama.

As a subject the circus is truly inexhaustible. Wherever I turn is a fresh picture, another angle. Life seems too short to put it all down. I come regularly to each performance and constantly make fresh discoveries. All the artistes know me and with a few minutes to spare, stand still in the entrance, just as if I have come upon them, gossiping, as they wait to take their turn in the ring.

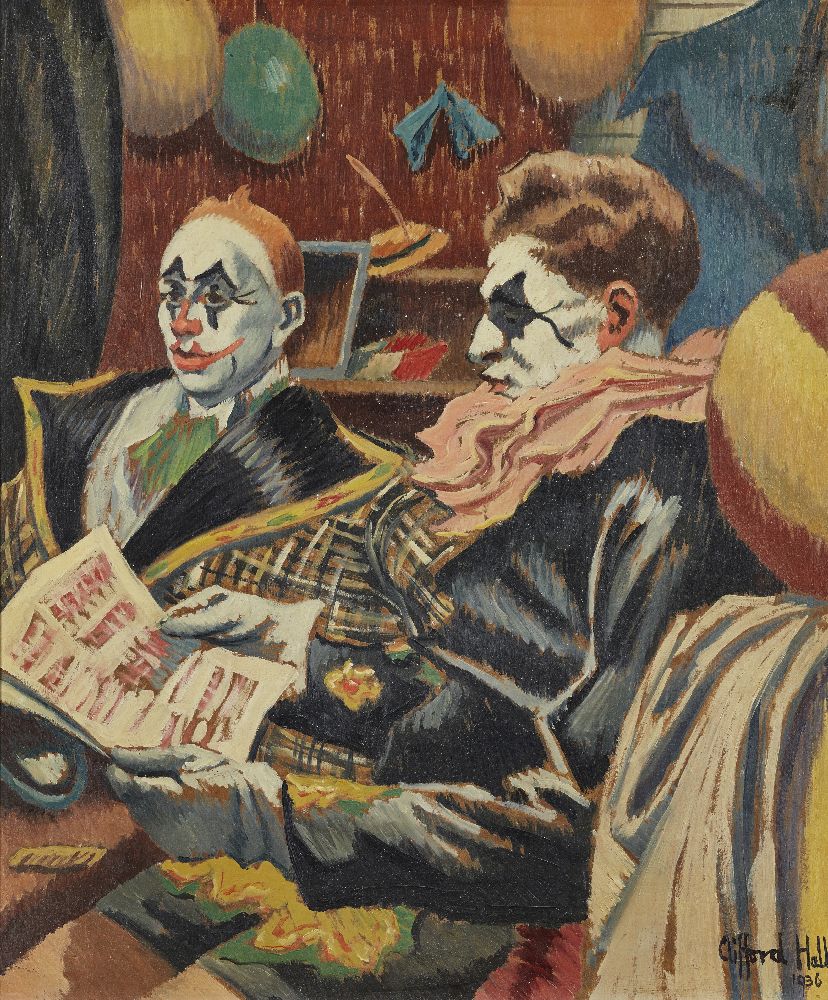

The intimate "behind the scenes' subjects give endless scope for painting. Seen in the half-light, away from the concentrated glare of the powerful lamps beating down on the ring, the clowns and Augustes, in their bizarre costumes and grotesque make-up, take on an entirely different appearance. The dressing tent, too, has a character of its own. All that stands for circus in the minds of old and young is displayed here in haphazard profusion. Costumes, balloons, false noses are suspended from the walls; improvised dressing tables holding their array of vivid greasepaints and wigs fill up every corner, yet the occupants still find room to play cards, fill in complicated football competition forms and even read snatches of an exciting detective story, while far off is heard the shouts of the audience and the rhythm of the music.

Every tune has a meaning for the resting clowns and suddenly, in a flash, the dressing tent is emptied. I hear the louder bursts of laughter which greets the appearance of the men who were so seriously occupied a moment ago.

I await their return outside. The night is lovely, the vast bulk of the Big Top is outlined in thousands of coloured lights. In the shadows, groups of performers make mysterious silhouettes, unconsciously composing themselves into new pictures for me. Out here the music is drowned out by the regular hum of the diesel engines generating light; from the direction of the menagerie I hear the roar of the lions.

The show is already preparing to move on to the next town. Whilst the last performance continues, the work of loading has begun. Strings of blanketed horses, their turn in the ring finished, move daintily across the ground as they are ridden away to the station, watched by the inevitable crowd of onlookers always present at the comings and goings of the circus.

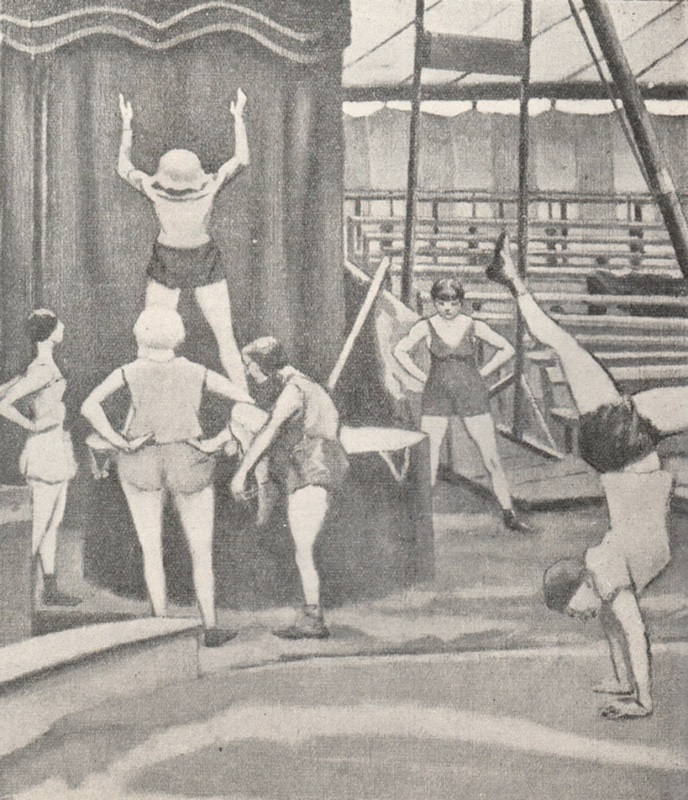

Whenever a build-up is not in progress, the performers practise. Almost every morning the Big Top is the scene of activity. Here again is my opportunity. I make rapid notes, take advantage of the comparative quiet to make closer studies of the various acts when tricks and movements are repeated over and over again in the artiste's search for perfection.

Practice costumes too show one a fresh aspect of circus life. A diffused light fills the vast tent: the canvas is a different colour now; without the huge audience one is conscious of a perfect forest of poles. In spite of the practice in the ring there is an odd air of stillness; the performers without their glittering dresses at last reveal themselves as real men and women.

It has often been suggested how much trouble and effort the artist could save if he painted his pictures from photographs. We all feel differently on these matters. Although I am convinced that the photograph has its place in the scheme of life, it seems to me that if a painter's work is to be of interest, it must be imbued with his individual reaction to the subject. I think that the only way one can hope to achieve this is by constant study and familiarity with the sounds and atmosphere of the circus as well as the people in it.

* * * *

The rapidity of the performance and the quick changes of lighting in the modern circus make it imperative to memorize much of the material for the completed picture. Colour must be remembered - not the obvious reds, yellows and blues, but the infinite changes and gradations that are brought about by the play of light which is also affected by the haze of cigarette smoke inseparable from a large audience.

To me, the very difficulties of trying to express the circus on canvas, are not the least of the factors which make the subject so absorbing and fascinating.

The CIRCUS MEMOIR, 1936

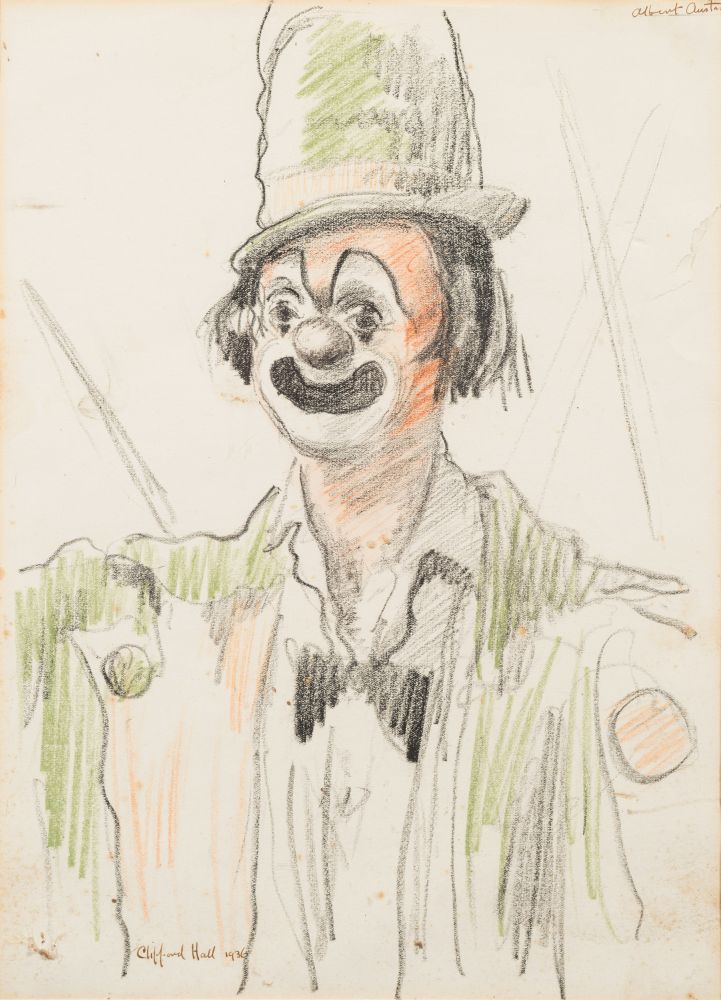

Albi Austin, the clown, 1936, by Clifford Hall.

Jack Lindsley's Orchestra Betram Mills Circus, by Clifford Hall. (no colour image currently available)

Clowns: Thomson and (Toni) Gerbola, 1936, by Clifford Hall. Photo credit: Roseberys Auctioneers, London.

The Clown on the Stairs, 1934, by Clifford Hall. (no colour image currently available)

Waiting for the Water Entrée, by Clifford Hall.

The Gold Act Girls at Practice, by Clifford Hall. (no colour image currently available)